HISTORY of DEAL: KENT: UK

Pictures and Stories of the Old Days

PAGE ONE

True Historic Story's

by

David Chamberlain

Click the youtube picture below to go to Dave's

channel there are lots of short films to view

Pictures and Stories are Copyright of Dave Chamberlain unless otherwise stated

David Chamberlain is a long established boatman

from Walmer beach from where he opperated his boat the Morning Haze

David has for years been recognised as a top charter skipper, operating from Walmer Beach. During his career, he has taken a great interest in the Goodwin Sands, from which he has been involved in many searches and artifact recoveries from wrecks on and around the Goodwin Sands

David has written several books on true events on the history of Deal which are all worth buying and reading.

He is a keen historian, and has great knowledge on the History of Deal.

This page contains True Historic stories and pictures produced by David Chamberlain

All of which should be of great interest to the reader

True Stories

By

Dave Chamberlain

"The Fearless of London"

At the turn of the last century sailing barges were a common site off Deal. These versatile vessels were the carriers of all types of goods and extensively used for the coastal trade. They used wind power and needed only a small crew. The next size up from the barge was the ketch barge, a larger version that not only did coastal but also short runs to the continent.

The ketch Fearless of London was 108 ton and had a length of 90 feet. On board were her master, Ernest Leek, and four crew. Part of his crew comprised of his twelve year old son, two seasoned deck hands and a greenhorn. Joseph Sennet was eighteen years of age and this was his first ever trip aboard a boat. He might have felt inadequate as Captain Leek’s young son had accompanied his father on many voyages and had more seafaring knowledge than him.

From Nieuwport, in Belgium, the Fearless had set sail on the 30th September, 1923 and her cargo was 200 tons of bricks destined for the port of Shoreham. Fog had chased the ketch all the way over the Channel … and when they narrowly missed the rocks that surround the foreshore off the South Foreland, Leek decided to anchor up in the Downs.

Less than a mile offshore, opposite the Time Ball tower, the Fearless found a good anchorage for a couple of days. Captain Leek knew the town of Deal. He had been rescued by the lifeboat in 1919 after spending a horrific night clinging to the mast of another ketch when it had gone aground on the Goodwin Sands. Perhaps Leek had a premonition of what was about to come, when he went ashore with some of his crew on the Fearless’ punt. With the barometer dropping, he had left Joseph Sennet in charge of his craft whilst he bought victuals for the next stage of his voyage - and despatched his son onto a train and back to his home in London.

Within three hours the north-west wind had freshened, with the making of a gale. As the tide made, Ernest Leek realised the sea was

too rough to get back to the ketch in his small punt. He quickly hired a Deal galley to make the trip, leaving the rest of his crew ashore. As he boarded his vessel he would have seen the look of relief on the face of the greenhorn crewmember, Sennet.

That night the full force of the gale erupted, creating heavy breaking seas which were swamping the deeply laden Ketch. With the lack of manpower, Captain Leek could not contain the ingress of seawater with the deck pump. As daybreak came, he reluctantly hoisted a signal of distress from the mast of the Fearless.

He and Sennet, were rescued from the sinking boat by the North Deal lifeboat and as they left the ill-fated Fearless they noticed the terrified ship's cat piteously mewing on the deck.

The ketch took the buffeting sea for the rest of the afternoon straining at her anchor. Just before darkness fell she slid beneath the waves leaving only her masts and the remnants of sails visible to those ashore.

Years later when the wreck was visited by divers, none of the wood remained of the ketch … only the pile of 200tons of bricks on the seabed showed that a tragedy had occurred.

************

"Death on the Goodwin's"

U-48

In the latter part of the First World War, German submariners were feeling the effect of the diligent Royal Navy and losses of U-boats were mounting up. Volunteers for the submarines dried up and the Kaiser had to resort in drafting men against their will into the service. Even the German populaces were feeling the affect of the British blockade and food was in short supply. When America joined the hostilities the war looked to be coming to an end.

The night of 23rd November, 1917, U-48 entered the Dover Straits en-route to intercept American troop ships coming in from the Atlantic. Kapitanleutnant Carl Edeling intentions were to pass over the anti-submarine nets placed beyond the South Goodwin's and proceed to the south coast of Ireland. It was never decided if the vessels compass was defective or the navigation officer’s calculations were at fault on that foggy night. Nevertheless, the outcome was that the U-boat ended-up stranded on the north Goodwin Sands.

With daybreak approaching, the captain of the U-48 knew they would be an easy target for warships of the Dover Patrol. Edeling had urged his crew to lighten the vessel and

they had discarded sixty tons of fuel oil. Next to be jettisoned was ammunition and three torpedoes. As the dawn light illuminated the Goodwin's, it was then that the submarine had just enough buoyancy to release her from the clutches of the sands. However, their fortunes were short lived.

The minesweeping Admiralty drifters that had left Ramsgate harbour were the first to sight the U-48. They sped in to attack the enemy and successfully managed to force her back onto the sandbank. Although the drifters were only armed with light deck guns and rifles they managed to hold their prey at bay until the destroyer Gipsy, alerted by the gunfire, pounded the undesarchiv (National Archives of Germany).

U-boat with her 4.1 and 22-pounder armaments.

The tired crew of the U-48 determinately fought the Royal Navy vessels, until her deck ran red with blood of the fallen. Kaptaitanleutnant Edeling decided that he was beaten and ordered the crew to abandon the craft after they had set charges in the forward and aft torpedo tubes. As the remaining crewmen swam away from their stricken vessel the twin explosions erupted leaving Edeling, along with half his crew of over 40 men, dead. The explosions awakened the

people of Deal on that grey winter’s morning and the survivors were taken back to Dover where the wounded were cared for.

From this action Lieutenant Commander Frederick Robinson RNR, of the Gipsy, was awarded a DSO plus £215 of the bounty paid out for destroying an enemy U-boat. The captains of the Drifters received a DSC apiece and the remainder of the £1000 bounty money.

After the cessation of the war the German prisoners were repatriated and several made claims of British brutality. In April, 1922, U-48s Leading Engineer, Willy Petersen, declared in the Amtsgericht District Court, under oath, that the British ships continued to fire at the German sailors who had abandoned their submarine and were swimming to safety. He also claimed that he was threatened with a revolver when he was interrogated to give information about other U-boat movements. When he was imprisoned at Lady Dundonald’s stately Welsh house Dyffryn Aled, he received harsh treatment, more threats and solitary confinement - which he thought unworthy of a German Officer.

Acknowledgment and thanks is given to Alec Johnson for the extra information obtained from B

************

"THE WRECK OF THE STRATHCLYDE"

The Early Morn was a fine North-End lugger and she was one of the swiftest on the beach. Throughout the 1870s she often won the Borough Members’ prize of £10 for the fastest in the Deal Regattas races. It would be her speed that helped save numerous people from the ill fated Strathclyde as she sank off Dover.

Captain Eaton was the master of the 1,255 ton steamship which was bound from London to Bombay. On board were 23 first class passengers and a crew of 47. Between four and five in the afternoon of February 17th, 1876 the Strathclyde was passing Dover Harbour steaming at 9 knots. On an adjacent course was the German steamship, Franconia.

As the Strathclyde eased her helm to starboard to make more sea room between the vessels, the Franconia altered her course to port and struck the British ship amidships, cutting through the deck to a depth of four feet. The passenger ship started to sink within minutes and Captain Eaton did his best to lower the lifeboats.

Fifteen women passengers and stewardesses were hastily ushered into the lifeboat, then some male passengers and crew took up the empty spaces. The extra weight made the lifeboat too heavy to swing out and away from the ship. The Captain appealed for the men to disembark for the sake of the women - and eventually the boat was lowered into the sea.

No sooner had the lifeboat cast off from the ropes that secured her to the davits the Strathclyde’s stern sank beneath the water. The suction created a maelstrom that capsized the lifeboat, tipping the women into the cold Channel waters. Then a large wave was caused as the ship completely sank and the remaining lifeboats and men were swept off the submerged deck.

Fortunately the Deal luggers Early Morn and Brave Nelson, along with the galley-punt Cruiser, were in close proximity. The skippers of these vessels were aghast as they watched the little damaged Franconia make for Dover Harbour – without any regard for the welfare of those floundering in the

sea. With great haste they sailed for the casualties and the Early Morn managed to save 24. Six more were picked up by the Brave Nelson and Cruiser, although two of them expired before they could get them ashore. Of the 15 women, only one survived.

Disgust was felt by the boatmen who had witnessed the actions of the cowardly Franconia’s captain. At Dover, a week later, he was arrested for manslaughter. The captain was found guilty; however, incredibly, months later the verdict was quashed on appeal.

Edward Hanger, skipper of the Early Morn would carry on saving lives as the second coxswain of the Deal lifeboat ,Van Kook (later to be named Mary Somerville). He retired from the National Lifeboat Institute in 1907 with a pension of £5.10s (£5.50p) and, being a fit and agile man, he was still skippering luggers until he was well over 80 years of age.

************

"ALL IN THE DOWNS"

This is the first part of a chapter in a book written by John Bickerdyke early in the last century about sea fishing in Deal. Also of the town and boatman. Well worth a read!

PART 1

Early one cold winter's morning I was lying gazing at Luke Fildes's pathetic picture of the 'Empty Chair', which hung framed on the bedroom wall, and was thinking of Dickens and Broadstairs and Bleak House, when the sound of a distant gun came echoing over the sea. A minute later there followed another faint 'boom', and the bell from the lifeboat-house clanged out a summons to the brave Deal boatmen to turn out of their warm beds and hasten away in the good boat 'North Star' to the relief of a ship in distress.

There was already a clatter of hurried footsteps on the roadway, and long before I could be dressed the lifeboat would have glided down the steep beach and into the sea; so, more or less philosophically, I turned me over for another doze, as it was yet early. But that doze was not to be. Presently in burst the little skipper, much excited with minute-guns and vessels in distress, and laden with the information that a foreign ship was aground on the Goodwin's, though there was no sea on, and the day was clear. There would evidently be no loss of life, but a good ship might be engulfed in those dread sand banks. The little skipper having exhausted his subject, turned his attention to a proposed raid on the whiting of the Downs, and informed me that Jonah, our commander in things piscatorial, said that the tide would serve us at ten o'clock, and Jonah had some lovely lugs (the said 'lugs' being the nastiest of the sea-worms), and Jonah would not be surprised if we caught a large cod, and Jonah had said this and Jonah had thought that.

"Now, get up, do !" ordered my little visitor in conclusion, and tripped downstairs for further converse with aged fishermen concerning their perilous adventures on the Goodwin's.Let it be understood at the outset that the little skipper was extremely youthful for the rank which had been conferred on him in our many fishing expeditions. In fact, he had not yet attained the mature age of ten; but, for all that, having commenced his life as an angler when only six by catching a cod of

Skardons World

nine pounds, and having a, perhaps inherited, love of things marine and fluvial, he was no mean fisherman and more handy in a boat than many a landlubber of double his age.We were staying in the quaint old portion of Deal, where houses with Dutch roofs, wooden balconies, and verandahs, attained by rickety wooden steps, are built in picturesque confusion more or less on the beach. The walls of little gardens are lapped by the waves of the equinoctial gales during spring tides. These gardens give great opportunities for smuggling on a small scale and the landing of wreckage from the Goodwin's. There is in Deal no scarcity of cigars or chunks of uncut tobacco which have not paid duty, and it is quite clear that some of the inhabitants are true to their ancient traditions.Nowhere are the coastguards more vigilant, a bronzed-faced blue-jacket inspecting most of the fishing boats as they come on shore unless they have been no great distance out to sea. But this is as much for wreckage as for undutiful tobacco or spirits.In this matter of wreckage the Deal boatmen propound a grievance. That which they gather from the Goodwin's they think should belong to them; but the Customs take it and only pay them salvage money. Thus one does not see at Deal, as in a certain Cornish village I could mention, the fisher lasses decked out on Sundays in Parisian gloves and Lyons silks, saved from the wreck of some unfortunate foreign vessel. It is good, no doubt, this rule as to salvage, but it is questionable justice when a ship is derelict and would in the course of a month or two be engulfed in the sand, that the poor boatman who fetches away from her a small cargo of spars and other timber, which would otherwise be lost, should only receive a fraction of the worth of it all.But this November morning the Customs concern us not, for we are bent on taking in a cargo on which no duties can be levied. Our little craft is named 'The Twins', out of respect to two maiden aunts of Jonah who bore that relationship to each other, and, on dying, bequeathed such a legacy to their nephew that he was able to buy the boat. 'The Twins' are - no, is - high and dry on the beach, just below the capstan, and quite thirty yards from the sea. Jonah asks us to get on board; then, we having obeyed, he looses the chain, and, at the rate of some thirty miles an hour we go, slap-dash, down that steep beach and into the sea, with a great splash, taking in quite a bucketful of water over the stern."I ought to have turned her", explains Jonah. "We usually come on to the beach broadside and haul up stern foremost, so as to get afloat bows first; but it was too dark and rough last night when I came in with the herrings, and we ha

************

"All in the Downs"

by John Bickerdyke

Part2

My fair-haired, blue-eyed little skipper busies himself hooking on the rudder and takes the helm, Jonah hoists the sail, and away we dance over the rippling water and head for the 'Gull' lightship. Jonah thoughtfully produces a small suit of oilskins, ancient but serviceable, and in these the little skipper is dressed, much to his delight. For a long time he sits in this fisher's garb, saying nothing but looking proudly seaward, and full of the sense of his responsibilities. Meanwhile our crew, a tall, black-bearded, reserved man, settles himself to a morning pipe and to get ready the tackle he deems necessary.

It is an offshore wind, and numbers of vessels are sailing through the Downs, the flood tide helping them on their journey to London or ports further northward. The wind is light, and every stitch of canvas is set. For a wonder not a steamer is in sight. Almost every kind of sea-going vessel seems to be in the Downs this morning. A great dandy-rigged barge with tanned sails comes gliding by us, and a topsail schooner a mile to seaward of us gently inclines her tapering masts to the breeze. Off Dover, and coming towards us, is that most beauteous of ocean birds - a ship under full sail. Jonah, by request, instructs the little skipper in the mysteries of spankers, main top-gallant stay-sails, foretopmast studding-sails, lower main top-gallant-sails, and others of the twenty or more grey wings which a three-masted, square-rigged vessel spreads in her flight over the sea. He points out to us barques and brigs, brigantines and yawls, and a somewhat uncommon vessel, coming in sight out of the haze off Dover - a three-masted schooner. Of luggers, hailing mostly from Deal, there is an unlimited quantity, but most of these have reached their fishing ground, and their crews are industriously endeavouring to gather in the harvest of the sea, principally represented hereabouts by whiting.

Jonah's marks are a tall chimney, a brick tree which grows out of the roof of the factory in which Deal sprats are turned into sardines á l'huile and a certain picturesque windmill. There is another pair of marks Doverwards, and, these having been brought into line, the anchor is dropped, the cable flies out, and 'The Twins' is brought up with a jerk - clear evidence, if any were needed, that a wild tide is running northward. Not only is the tide wild, it is also eccentric and unlike other tides, for it runs towards Ramsgate for three or four hours after high-water. We are to fish, says Jonah, on the 'ease of the flood and draw of the ebb'; and it is very evident that at present the flood

Dave Chamberlain

is un-'easy', for no leads that we have in the boat are heavy enough to hold the bottom. The little skipper is mildly indignant, and asks how we are to catch anything when his line is streaming out astern and several fathoms above the fish. Jonah counsels patience: the tide will soon ease, he says.Ten minutes later I find I can hold the bottom, for I am fishing with a fine silk line which offers little resistance to the water, and no sooner does this happen than there come a couple of sharp jerks at the top of my short rod and I wind up a lively whiting of a pound or more.Every minute now the current grows less strong, and the little skipper, who is fishing with a stout gut paternoster fastened to a fine handline, hauls up his first fish. To his great disgust it is a spurdog, a spiteful-looking miniature shark, which can inflict a poisonous wound by means of a spike placed behind its dorsal fin. Jonah handles the fish with extraordinary care, and cuts off its head before attempting to dislodge the hook from its mouth. While this is going on I land two more whiting, and Jonah begins to look with more respect than he has hitherto done on my rod, reel, and gut tackle. I am to convert worthy Jonah today, for the water is clear and there is no wave, so that in all probability his coarse handlines will catch but few fish. His arrangement of chopsticks, blunt tinned hooks, and hemp snooding is now hauled up. The baits are intact; not a fish would look at them.

Before Jonah can let down his line the little skipper shouts joyously that he has another fish - a big one - and, handling the line tenderly to prevent a breakage, brings up two silver whiting at once."Odd I don't get ere a bite", says Jonah, more to himself than to us, as he flings the fish into the bottom of the boat. "Well, if there ain't another !" for I am winding up my reel, and the rod-top is jerking violently. I am hoping that it is a very large whiting which has taken my bait, but it is nothing more than a spotted dogfish, which fights gamely for his life. I regard my capture somewhat contemptuously, and ask Jonah why he does not treat it as he did the spurdog."Throw that overboard !" says

our commander slowly, with a strong Kentish drawl; "why, that fish's worth more'n a whiting. I could get twopence for he. They eat he hereabouts."We live and learn truly. Here is a fish which I had always cast away, and had only once heard tell of a man (and that man a French sailor) eating, and yet at Deal it is held in higher esteem than whiting. We will do as Deal does. That fish shall figure on the dinner-table, but with one of another variety in reserve should it prove uneatable.The next capture is a small whiting on the thick handline. Jonah hauls it up smartly, remarking complacently that he knew he should get something soon. But when the little skipper and I have between us caught eighteen silver whiting to four taken by our crew, that worthy remembers he has a bit of gut in his pocket a gentleman once gave him, and ties it on, henceforward catching about as many fish as we do.The tide eases until it is easy indeed, and our lines go down close to the side of the boat. The fish begin to bite shyly, and to meet their views I put on tiny hooks and small fragments of bait, which proceeding further astonishes Jonah, more especially as the alteration leads to the capture of half-a-dozen fish while the other lines are catching nothing. Then we get no more bites, and Jonah says we shall catch no more until the 'draw of the ebb'. So we refresh the inner man and hold a conference on whiting and their ways. Jonah confesses himself converted on the subject of fine tackle for sea-fishing, and we pass a resolution that our modern methods of sea-fishing are, when the water is clear, an advance on the tackle used by the fishermen. In coloured water, or at night, we know that the tackle which will haul up the fish quickest is the one which will soonest fill the basket.

************

"All in the Downs"

by John Bickerdyke

Last part

The sun is setting behind Deal, and the whole town is bathed in golden vapour. The wind has fallen, and the sails of the ships hang down and flap against the masts as the vessels roll slightly from side to side. I look regretfully at the old portion of the town, with its red Dutch roofs and quaint old houses, built on the beach - picturesque objects

which an improving (save the mark !) town council proposes in part to sweep away to lengthen an already overlong parade. To the northward is another instance of vandalism - the remains of a castle, with walls five yards thick, commenced by Bluff King Hal, and finished by good Queen Bess. All is levelled save the dungeons, and because, forsooth, the sea was encroaching and undermining the foundation. Was not such an ancient landmark worthy the few hundred pounds which would have enabled proper protection from the sea to be made ?

This old fortress has a place in our history, for here it was that Colonel Hutchinson, one of those who signed Charles the First's death-warrant, was imprisoned. His room had five doors, it is said, and the unfortunate gentleman was literally killed by the currents of air which played about him in winter. The castle is described as having been at that time a poor dilapidated place

garrisoned by half-starved guards, who were eaten up with vermin and cheated out of half their pay, spending the other half in drink. The War Office sold the castle for building material not fifty years ago. It realised something over £500.We are now facing southward. The first capture is a dogfish, which the boatman handles carelessly enough, explaining that this one is a 'sweet William and real sweet eating'. In appearance it is exactly like the little blue dogfish which we caught earlier in the day, but it is without the dangerous spur on its back. Soon the whiting bite as merrily as ever, and the floor of the boat is littered with the slain. "Shouldn't wonder if we hadn't five score", says Jonah, and sure enough when we count the fish that evening there are no fewer than a hundred and seven of them

But whiting, spur and spotted dogs, and Sweet Williams, are not our only captures. Before the anchor is raised half-a-dozen flat fish are flapping their tails on the bottom of the boat. A stray codling greedily swallows both the baits on the little skipper's line, and the inevitable hermit, or king, crab, whose hermitage or palace, as you like to put it, is a whelk shell, of course makes his appearance. He tumbles into the bottom of the boat immediately he is hauled over the side, retreats into his shell for awhile, then he protrudes his legs and begins to crawl about among the dead and dying whiting, carrying that mansion of a departed whelk on his back as usual, A small conger, too, creates a small excitement on board, and mixed with the silver whiting are a few pout.The 'draw of the ebb' increasing to such an extent that we can no longer hold the bottom, Jonah weighs the

anchor, and, each of us taking an oar, we row home. Cold and darkness set in before we reach the beach; but we dread neither, having a good pilot in Jonah, and means of keeping warm in our hands. We take the beach broadside on, the rudder is unshipped, and 'The Twins' is hauled ignominiously, stern foremost, over the shingle, three weather-beaten, pilot-jacketed friends of Jonah running round the capstan. We ask one of them what happened to the lifeboat in the morning, and learn that a tug from Ramsgate arrived before her at the Goodwin's and towed off the stranded vessel.Our pleasant day in the Downs has come to an end. We feel grateful for the cheery fire which blazes in our cosy room. But our work is not yet over, for baskets of fish have to be sent to country friends by an evening train. That done we sit down to fried whiting and twopenny nurse-dog, and pronounce the latter sweet, soft, and watery, and we decide that the French sailor was unworthy of his nation, and that the people of Deal are, to say the least, peculiar I tastes.

************

I don't often do book reviews, especially when they are over a 100 years old ... however.

Father and Son

Two little known books about the boatmen of Deal were written by a father and son, who managed to capture the atmosphere of the town in the late 1800s. William Clark Russell’s book ‘Betwixt the Forelands’ is a historical narrative of the importance that the Downs, between the North and South Foreland, played in the past. He had

grasped the significance and portrayed it in his book; as W Clark Russell had a full and credible knowledge of all seafaring aspects and would have conversed with the old salts on Deal beach. Born in 1844 he had joined the Merchant Navy at the early age of 13 as a midshipman who wage was a mere shilling (5p) a month. The eight years of service he had done was to affect his health for the rest of his life. His duties were of the gross kind which a normal seaman would have refused to do.He became a prolific writer with one of his novel’s ‘The Frozen Pirate’ bordering on a science fiction equivalent to Jules Verne, where a shipwrecked mariner brings back to life a pirate who had been frozen in ice for

centuries … with dire consequences. At the time of writing ‘Betwixt the Forelands’ in 1889, Russell’s abode was at 3, Sandown Terrace, Deal. His time spent on the beach talking to the old boatmen was not wasted and the full flavour of Deal’s past is to be tasted in the tome.‘The Longshoreman’ is a much sort after novel and is hard to find. This book was written by W Clark Russell’s son, Herbert, at the age of 27 years in 1889. The novel describes the antics of Deal boatman and a mysterious financial backer seeking treasure from the Goodwin Sands. His description of the Deal boatmen and their adversity trying to earn a crust against the storms that kept them

ashore is truthful; and gives a marvellous insight of the hardships that they suffered.It is a strange tale set in the late 1800s, where the Deal lugger Tiger was chartered for a week by a London visitor and financed by a Mr Morgan. Their quest was to dig for buried treasure on the Goodwins. It was said that the Tiger was put ashore on the sands at low water and, with the aid of a large metal cylinder, the party dug a shaft within it. The men soon encountered a skeleton and then a wreck. Further burrowing in the hulk’s timbers found the holds ‘as dry as an empty bottle’. Nevertheless, at the end of the week, a dozen chests of treasure were loaded onto the lugger and the expedition was hailed as a success.Prior to the finding of the treasure,

the hero of the novel realistically describes his life as a Deal boatman. His adventures border on smuggling, hovelling, pilot work and lifeboat saves.This is how it was told in Herbert Russell’s novel, but the only truth from the narrative is that the Tiger was a real vessel and the largest lugger on Deal beach throughout the 1890s.

For authenticity, many of the characters in the story had the surnames of Finnis, O’Bree, Budd, May, Porter, Stanton, Erridge and Meakins - whose relatives still live in the town today.Herbert Russell was born in 1869 and carved a successful career in journalism. He went on to be one of the few journalists to be selected by the government to cover the World War One on the Western Front. He continued working for Reuters and at the end of the

conflict he was introduced to King George V in 1917. His Royal connections lasted into the 1920s when he accompanied and reported on the Prince of Wales’ tour of India and Japan. He continued as an author writing many books on military matters as well as novels. He died in 1944 at the age of 75.

************

"Death in the Channel"

The Dover Straits was shrouded in fog on the night of the 19th of November, 1887, and the 720 ton West Hartlepool steamer Rosa Mary was anchored up near the South Sand Head Lightvessel (South Goodwin). Her anchor light was shining from the masthead and a few of her 16 hands were keeping a look-out from the bridge.

In the swirling mist the Red Star passenger ship W.A.Scholten approached the anchored vessel. On board were

156 passengers and 54 crewmen. She had sailed from her home port of Rotterdam earlier in the day and her destination was New York. Many of the passengers were seeking a new life in America and the 2,569 ton Dutch steamship had families and children in the steerage class cabins of the vessel. On a steady course and slow speed of six knots the W.A.Scholten continued towards the Rosa Mary.

At ten-thirty Captain Taat saw the anchored collier ahead of the passenger ship and at the last moment ordered full astern on the ship’s telegraph. In the cold night air the sound of grating steel and wrenching plates were heard as the W.A.Scholten ripped off the bow of the Rosa Mary to her inner bulkhead. An eight foot gash was also torn along the port side of the Dutch ship as she disappeared into the mist.

When the forward way of the W.A.Scholten ceased, the strong ebb tide was to carry her on for another four miles. The sea was gushing in through the hole and pandemonium broke loose as the immigrants realised that the ship was sinking. Screaming passengers careered about the deck as the crew attempted to get the lifeboats away. Only two were launched before the sloping deck plunged below the cold waters of the Channel. Within a mere thirty minutes all that remained of the ship were her masts protruding from the sea.

It was the heartbreaking screams of the drowning families that alerted the crew of the British steamship Ebro, who managed to rescue 78 people.

Dave Chamberlain

The other ship involved in the collision, Rosa Mary, limped into Dover Harbour with her bow watertight bulkhead still intact.

As many bodies washed up on the beaches of Deal it was deemed that the town should hold the inquest. From the findings some startling statements were made. A Hastings fishing boat’s skipper stated that the Rosa Mary had been underway prior to the collision and had ploughed through his herring nets. Parts of his nets were found on the mangled remains of the steamers bow. Some of the survivors accused the W.A.Scholten’s Captain Taat of keeping the steerage passengers away from the lifeboats. The captain could never defend himself as he and the first officer perished with their vessel. There were enough lifejackets on board for all, but many of the passengers had put them on incorrectly (as some of the recovered bodies had later shown) so inadvertently adding to the death toll.

************

Another ship on the Goodwin's

Within ten minutes of the maroons being fired the Walmer lifeboat Charles Dibden was launched from the steep beach. The weather was starting to deteriorate with an increasing southerly breeze that was clearing the sea mist. As the lifeboat got clear of the land on that cold day of January 2nd 1948 the crew started to feel the vessel roll and pitch as they approached the Goodwin Sands.

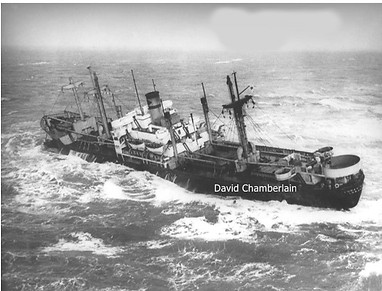

An hour earlier, as the fog dispersed, a ship had been sighted by the Deal coastguards in an unusual position close to the deadly sandbank. As the Charles Dibden approached the casualty her skipper, Freddie Upton, found the seas in a confused state. With the tide falling and the wind freshening the waves started to become unpredictable and perplexing. The stranded ship turned out to be the 290 feet long Silvia Onorato, an Italian cargo vessel of 2,327 tons.

Cautiously Upton conned the lifeboat closer to the casualty, however, by this time the waves were building up and cresting to an uncomfortable

height. One wave, larger than the rest, lifted the lifeboat to enable her crew to look down onto the ship’s deck. As the sea receded the Charles Dibden scrapped down the vessel’s hull, fortunately doing little damage to the rescue craft. Upton managed to get a crewman aboard the Silvia Onorato and Captain Francesco Ruocco explained that he was prepared to try and steam the ship off the sandbank at high tide.

Ruocco’s futile attempt only drove his vessel off one sandbar onto the next sandbank. The ship’s propeller churned up sand and spray, in only 14 feet of water the vessel needed at least 20 feet to float off. With the weather worsening and the tide falling, Upton put the lifeboat alongside the hulk and picked up his crewman. He explained to the Italian captain that they would have to anchor off in deeper water, nevertheless, if any emergencies occurred he would respond immediately. It would be an uncomfortable night that they spent with only a meagre supply of rum ration to help.

Hardly any of them slept and just before dawn they had up-anchored and were alongside the ship again. The lifeboat coxswain explained that they had to go ashore and refuel and they would be back within a couple of hours. True to his word they returned and stood by for a second day and night, as the weather worsened and the wind reached gale force.

Daybreak on Sunday, 4th January not only heralded another rough day but also was Upton’s 51st birthday. When he went alongside the

Above the Walmer Lifeboat; Charle Dibdin,Right on January 2nd 1948 Silvia Onorato, an Italian cargo vessel of 2,327 tons. gets stranded on the Goodwin Sands

Silvia Onarato her master stated that the vessel was sound and he did not wish for himself or his crew to vacate the ship. Upton took the lifeboat back to the Walmer station for the boat to re-fuel and her crew to have a meal.

Inside a few hours the Charles Dibden was back alongside the ship. Freddie had had a warning from the coastguards that the gale was going to increase to a storm and winds of fifty knots were predicted. It was enough to convince the Italian and he reluctantly allowed his 28 crew, two stowaways and himself to be taken ashore. The ship never survived the gale and broke her back to remain forever on the Goodwins.

************

"An un-happy Christmas"

On Christmas Eve, 1946, the skyline east of Deal was to be blighted by the sight of a shipwreck which would remain for almost fifty years. In foggy conditions the 7,612 ton Northeastern Victory raced up Channel to enable the skipper and crew to spend Christmas at her port of destination, Antwerp.

Captain Kohstrohs either did not hear, or ignored, the warning cannons being fired from the South Goodwin lightship as they hurtled past. The Victory ship’s 6,000 horse power engine was at full speed and this, coupled with the assistance of a spring tide, was propelling the vessel at a speed of 21 knots.

Kohstrohs’ charts of the area did not advise of the dangers from the Goodwin Sands and the American War Administration felt the use of pilots a wasteful source of finance. Within five miles of passing the lightship the Northeastern Victory came to an abrupt standstill as she ran onto the Sands. The force of the grounding carried away her radio aerials making communication useless … and in the swirling fog, her master realised it would have been pointless to set off flares.

Luckily the ever alert Deal boatmen realised that the South Goodwin Lightship’s warning cannon fire meant

that there could be a chance of trouble. It was left to old Joe Mercer, in the beach boat Rose -

The NorthEastern Victory

Marie, to go and investigate. An hour later he came up against the slab-sided hull of the Victory ship high and dry on the Goodwins. Joe realised that the vessel was doomed and informed Captain Kohstrohs that he would summon the lifeboat.

At five minutes past five that afternoon the Charles Dibden launched in darkness into a calm sea. Coxswain Freddie Upton soon found the casualty and took off 36 of her crew. Only the Captain and six officers stayed aboard the stricken hulk. As he left, Upton noticed a two foot gash had already appeared across the deck of fated ship. By 10 o’clock that night the lifeboat had offloaded her human cargo and had returned to the shipwreck.

As the wind freshened, the men spent an uncomfortable night on the lifeboat, which was standing by the wreck. Their only consolation, apart from a ration of rum, was some turkey that had been prepared in the Northeastern Victory’s galley previously. Christmas Day was greeted with a blood red sky. True to the weather saying of ‘Shepherds warning’ the Charles Dibden’s radio came to life with a gale warning from the Coast Guard. After a brief discussion with the cargo vessels captain, Freddie convinced them it was time to leave.

Over the years the masts of the Northeastern Victory could be seen from the beaches of Deal as a prominent reminder of the dangers of the Goodwin's. In January 1995 the remaining rusting mast disappeared in the aftermath of a winter’s storm. Fondly known as the ‘Sticks’ to the Deal boatmen, it was yet another part of Deal history to fade away.

************

"Goodwin Sands Treasure"

Over hundreds of years, the 10 mile stretch of sand called the Goodwin's has been the demise of thousands of ships and their crews. This natural hazard has trapped and consumed the unwary captain and his vessel by misfortune or mistake. Fog, storm and miscalculation are various acknowledged reasons of ships being wrecked on the Goodwin Sands … as well as some in mysterious circumstances.

The shifting sand would consume many ships and the riches of their cargo would lay undisturbed for centuries. However, it would be the weather and tide scouring the ever shifting sandbank which could expose these shipwrecks over a period of time. When this happens, fishermen inadvertently snag their nets on these uncharted obstructions and note the position on their GPS plotter. The Longitude and Latitude of the mysterious seabed hindrance are sometimes given to sport divers to investigate – and this is how new shipwrecks are found and named.

This is what happened in 1982, and divers were amazed to locate a shipwreck of the English East India Company full of coins and copper ingots. The Admiral Gardner was an outward bound sailing ship with a full cargo of goods that went aground on the west bank of the Goodwin's in January, 1809. At the time of finding, the wreck was outside the jurisdiction of the Government and an intensive salvage operation took place. From the remains of her holds, most of the 46 tons of newly minted coins were reclaimed in small wooden barrels that held 26,000 in each.

Eventually, in 1989, the British Government gained the control of 12 miles from the coast and made the wreck site protected. By this time only some cannon and ferrous goods remained and the archaeologists had little to discover. As the years went on, sand started to build up over the wreck and it was last reported that at least 25 feet of sand has covered the remains of the Admiral Gardener.

A more recent find is that of the Dutch East Indiaman Rooswijk which became exposed near Kellett Gut on the Goodwin Sands. Although a government protection order was put on the wreck, it was acknowledged that it still belonged to the Dutch Government; even though it was lost in 1740. Her cargo comprised of 100 bars of silver and 36,000 pieces of eight. Most of these coins contained a regular 26.5 grams of .903 fine silver.

Throughout the summer of 2005, the 209 ton dive vessel, Terschelling, recovered the boxes of silver bars and the coins. On board was a diving archaeologist who recorded the finds and remains from the ship. Most of the relics were presented to Holland at a ceremony aboard the Dutch Navy frigate De Ruyter, at Plymouth, later that year.

The secrets that the Goodwin Sands hide, at the moment, lie undisturbed; however, perhaps over the coming years, with the storms that batter our coast, more shipwrecks will be found and the wealth of Britain’s maritime heritage increased.

************

"The Loss of the James Harrod"

Thirty-one year old Lieutenant Adolph Hoehling had just taken over as leading officer of the United States Navy gun crew aboard the SS James Harrod. Like all Liberty ships she was named after a famous, or not-so famous, American citizen. Her namesake, James Harrod, was an 18th century Kentucky frontiersman and Indian fighter, who founded Harrodsburg. When the ship left the navy yard in South Philadelphia she was laden with 9,200 tons of high octane petrol in 5 gallon cans and a deck cargo of Lorries for Europe. This was to help in the mopping-up stages of the Second World War.

The James Harrod had sailed through the Atlantic unscathed and was bound for Antwerp. As she entered the Downs at just past midnight on Tuesday 16th January, 1945, it was noted that the wind was light with a slight mist and a strong 4 knot current attributed to the spring tide. When the ship slowed down to 5 knots these tidal conditions made it difficult for the helmsman to steer a straight course. As the ship approached the busy southern anchorage off Walmer, Lieutenant Hoehling was on the bridge and in radio contact with all of his gun crew; who were standing by in their helmets and life jackets at general quarters. Although the Second World War was almost over, there were still enemy aircraft waiting for an easy target. Through the starboard wheelhouse window the Lieutenant noticed a speck of light. This turned out to be the anchor light from another Liberty ship, Raymond B Stevens - which was directly in their path. When Hoehling realized that Captain Karsten

had not seen it, he shouted the command to the helmsman to steer to port and reverse engines. The order was given too late and the James Harrod collided with the anchored vessel at 01.25 hours on that dark cold morning.

When the bow of the Raymond B Stevens ripped through the other ship’s side, it pierced number four hold by 10 feet and sheared off all of the starboard lifeboats and rafts. Alarm bells sounded-out on both ships as they lay impaled. Suddenly, smoke and then flames started to rise from the side of the James Harrod as her cargo of petrol ignited. One of the aft gun crew, Seaman First Class James (Rebel) Ricketts jumped from the stern - and Mary Lou Ricketts, of Homer, Louisiana, would lose her third and last son to the war. Ricketts body was never found and would be listed as missing in action.

The Liberty ship Raymond B Stevens was fully loaded with ammunition bound for the continent, which made her a potential time bomb. Their crews raced to the ship’s bow and hosed water onto the James Harrod as they quickly hauled-up their own anchor to get away from the flaming casualty.

Most of the James Harrods crew were screaming, not because they were injured but in pure panic and abject fear.

Nevertheless, someone had the initiative to give the command to stop engines and drop anchor. If the ship had drifted through the crowded anchorage there would have been a calamity that was not worth thinking about. They lowered the remaining two lifeboats on the portside and dropped the cargo nets for the survivors to scramble down and board them. As the first boat pulled away, gunner’s mate Third Class, Graydon Taylor, who was 22 years of age and only just married, attempted to swim to it. His body was washed ashore at Deal days later. Lieutenant Hoehling watched as Walter Porter, another of the gun crew, jumped into the freezing sea and swam to the remaining lifeboat. The 19 year old, who was a motorcycle enthusiast, was pulled out of the water by the ship’s lifeboat crew. However, the cold sea had got to him and as hard as they tried to revive him, he was declared dead.

A further member of the naval gun crew who did not survive was Seaman First Class Paul Thompson, who prior to the voyage had recuperated from a hernia operation. These were the only fatalities from the United States Navy crew as the rest of the merchant seamen survived.

With 37 persons in the first lifeboat, it was left up to the remaining one to secure the rest of the crew from the cargo net which was hanging from the hull. As it pulled away from the ship, only a handful of men remained on the blazing vessel. One of them was Lieutenant Adolph Hoeling, who had gained some respite from the flames on the port side of the James Harrod. In the acrid stench of burning petrol, he searched the deserted cabins to make sure there were no injured or men who required help. As he went back on deck, the elderly captain was there with the chief engineer and signalman and a few others from the merchant and navy crew.

The fire, by this time, had reached its height with flames soaring almost 200 feet into the air and 5 gallon flaming petrol cans also being propelled skywards. All along the starboard side of the James Harrod, the sea was a mass of flames. Their hope of being rescued was fading fast as no other vessel would go anywhere near the ship for fear of a mass explosion from the petrol or the guns ammunition. Just as the group was deciding to jump into the cold uninviting sea, they spotted a small ship approaching. This vessel was the Tromp, a Dutch coaster that had just returned from Antwerp. Slowly as she went alongside the stricken ship, the Dutch skipper, Harman Heida, shouted for the men to jump.

The last to leave the burning ship was the Liberty’s elderly Captain, Hugo Karstan and Lieutenant Hoeling. Both received injuries from the 15 foot drop onto the Tromp’s deck, however, all survived their ordeal. As the Dutch ship anchored-up a 1,000 yards from the burning Liberty, the survivors and Dutch crew awaited daylight. Morning brought a team of fire-fighters from Deal who strived to subdue the flames. Their task was eventually successful and the slowly sinking James Harrod finally stranded in the shallow water off Deal Castle.

************

"LIGHTSHIPS AT WAR"

At the outbreak of the Second World War the crew of the North Goodwin lightship had front row seats to the beginning of the conflict. Initially, they were to witness the ships and boats ferrying British and French troops away from the beaches of Dunkirk Then the Luftwaffe bombing and shooting up the allied shipping. They heard the drone of enemy aircraft on moonlit nights and the ‘plops’ as magnetic mines were being dropped. Along with the autumn equinox and wintry gales, mines that had broken loose from their moorings were yet another threat.

However, the captain and crew felt that they were in little danger from the enemy, as in the last war the lightships were left out of the conflict on humanitarianism grounds.

Nevertheless, when they heard the chilling broadcasts of ‘Lord Haw-Haw’ declare that ‘…Aircraft of the Third Reich have been fired on by armed enemy lightships in the Thames Estuary.’ they knew that they had now become a target. They were puzzled by this statement, as they did not even have a rifle on board to sink the drifting mines. In actual fact the only armament that they carried was the black powder loaded cannons they

used for signalling a hazard to other vessels.

As the days went by, their attentions were to be focused not only on the sea but also the sky. They did not have long to wait.

Three J.U.87 dive bombers came from the east and made a be-line for the lightvessel. One bomb screamed down so close that it sheared off its vanes as it hit the vessels deck rail and exploded in the sea. This was just a taste of things to come.

Over the next few days other lightships in the area got a pasting. The East Goodwin was sunk – luckily her crew had been evacuated earlier. When the North Goodwin’s crew saw a swarm of 25 Dorniers, along with a fighter escort, they donned there tin helmets and looked for somewhere to take cover.

Bombs rained all around them and the stench of burnt high explosive offended their nostrils. Churned up muddy seawater cascaded over the men and lightship’s deck; bomb splinters rattled on their steel helmets.

As the aircraft passed, they looked around them. Miraculously there were no casualties – only a multitude of dead fish floating on the sea.

Within hours they received orders that the following morning they were to be evacuated from their ship. At three a.m., out of the darkness, an admiralty trawler came alongside. With haste, the captain and crew of the North Goodwin threw their kit bags on to the trawler’s deck and climbed down the Jacobs ladder into the awaiting vessel.

After this event the lightship was only visited occasional and it was only at the end of the hostilities that they were replaced and fully manned again.

************

"LIFEBOAT VICTORY"

Up until recently there was only one wreck that was visible with the naked eye on the Goodwin's Sands. It is hard to believe that the massive 7,612 ton Luray Victory’s former glory was reduced to a king post showing above the sea. However, even this piece of wreckage disappeared over the summer months of 2018.

On January 30th 1946, the Luray Victory, which was only two years old and operated by Black Diamond Steamship Co, was on route to the port of Bremerhaven. From Baltimore, the American government was sending vast amounts of food supplies to relieve war torn Europe.

However, according to the recommendation of the American War Shipping Administration their ships did not require pilots to steam through the Straits of Dover. The charts on these Victory ships were not even amended or updated with the inclusion of the buoys that surrounded the Goodwin Sands.

On that cold January night, coxswain Freddie Upton along with his lifeboat crew were returning from a wasted trip out to the Sands in an area known to them as ‘Calamity Corner’. The vessel that they had searched for was the American Liberty ship Am-Mer-Mar. She had inadvertently gone aground on the Goodwin's, but had managed to free herself before the lifeboat had arrived.

Shortly after the Walmer lifeboat Charles Dibden had returned ashore, Upton was informed that another American vessel had gone aground in the same vicinity as the last. At twenty-seven minutes past ten they came

upon the ship. She was almost high and dry in the near gale force wind and the seas that surrounded her were a turbulent mass.

Freddie Upton considered it too dangerous and an unnecessary risk to his crew to go along side the grounded vessel, therefore, he waited for the tide to make. Later that night tugs arrived and, as the tide rose, the Charles Dibden assisted them in getting a towing hawser aboard the Luray Victory. Unfortunately the Goodwin's had already made a prior claim to the ship - as the tugs efforts were in vain.

The crew of the lifeboat were tired and famished as they had spent all night five miles offshore in those inhospitable conditions. After the Charles Dibden was refuelled and the men had put on dry clothes and satiated their hunger, Upton returned to the strickened casualty

By this time the wind had reached gale force and had backed to the south. As the lifeboat coxswain reached the Luray Victory, he could see that the ship was starting to break up. The Goodwin's had broken the back of the 439 feet hull which was now listing to port.

At four o’clock on that wind swept afternoon the captain of the Victory ship declared that he wanted to abandon her.

The lifeboat cautiously moved towards the vessel. With low water approaching the seas were crashing against the sides of her hull, also the ebb tide was sluicing along it making the conditions worse. With the help of his engineer, Upton managed to bump the lifeboat alongside the wreck, enough times to take off the entire ship’s crew of 49 to safety and dry land.

The Lurray Victory ashore on the Goodwin Sands

************

Deal and ‘The Great Storm’ of 1703

With a fresh south westerly wind blowing on the 22nd of November, 1703, a British naval fleet comprising of large first, second and third rate ships-of the-line limped into the Downs to anchor. Under the command of Admiral Sir Cloudesley Shovell, they had had an unsuccessful expedition to the Mediterranean with not finding their French enemy.

Since the engagement was ill planned and rushed so late in the year, the sailors aboard the vessels had endured hardships with lack of victuals and on short rations. Because of this all three of the hospital ships, that followed the fleet, were full of men who had not been hurt in battle, but were malnourished and feverish. Many of the ships logs had recorded DD (Discharged Dead) against seamen’s names in the muster lists. The massive three and two deck vessels joined the smaller ships of the Channel Fleet, which were already in the crowded anchorage sheltering from the weather.

As the wind increased, it was clear to the admiral that his larger ships needed more protection. Their towering hulls would catch the blustery weather and making tides, which would cause the ships to drag anchor. Sir Cloudesley Shovell ordered these vessels to up-anchor and proceed to the River Medway for their own protection due to the inclement elements. He left his smaller third rate and one second rate men-of-war under the control of Vice-Admiral Sir Basil Beaumont, who was commander of the Channel Fleet already in the Downs.

Within the week gales were occurring continuously and the anchorage became full of merchant as well as Queen Anne’s naval vessels.

On the night of 26th November, strong spring tides and an increase of wind to storm force alerted the captains to what a precarious position they were in. Some let out more anchor cable and others dropped a second anchor to ride out the storm. In the early hours of the morning the wind increased to hurricane force and, at times, blew over a hundred mile per hour.

With a new moon, the Downs was in total darkness and indistinct shapes of ships could be seen dragging their anchor and entangling with other vessels. The wind was so strong that the officers’ orders could not be heard or carried out – although in the circumstances, there was little they could do against the vehemence of the elements. Cold spray was lashing the men and chilling them to their inner core as they struggled against the wind. Masts were cut away to try and steady the ships along with the ropes and spars that were ensnarling each other. Whilst this was happening some of the naval men-of-war were slowly furrowing the seabed with their anchors towards the perilous Goodwin Sands.

As daybreak reluctantly broke on the 27th November, the wind was still blowing storm force, and from the town of Deal, observers on the wave tossed foreshore could see the devastation in the anchorage. All of the one hundred and more ships were in disarray, many with masts gone and complete chaos on board. Four wrecks that were displaying signals of distress were seen on the Goodwins and their size showed that they were British naval ships.

Thomas Warren, future mayor and in charge of the Naval Yard at Deal, consulted with the boatmen how a rescue could be attempted. They all agreed that the sea was too rough to launch a boat from the beach and it would be an impossible task under those conditions. All that day the townsfolk watched with sympathy the plight of the men on the disappearing stranded warships as the tide made once more. An attempt by the large man-of-war, Prince George, to launch a long boat to save the shipwrecked men was futile as they could get nowhere near the wrecks. The survivors on the 70 gun Stirling Castle, Restoration, Northumberland and Mary had to cling-on to their battered remains and endure another night under those appalling circumstances.

The following morning three of the wrecks had disappeared and only the Stirling Castle could be seen still showing above the waves. Her anchor had dragged to an area called the Bunt Head, in the shoal water surrounding the Goodwins. Tides in the shoal water were not as strong and had been her salvation against the fury of the storm. With the wind decreased, boats managed to get afloat and save the lives of 70 seamen from the wreck, leaving on board the bodies of many others who had died of exposure and hypothermia. The Goodwins eventually consumed the vessel - along with its dead.

Note: The wreck of the Sterling Castle was discovered emerging from the Goodwin Sands in 1979 where many artifacts were recovered by divers.

************

The Piave's Maiden Voyage

In the nineteenth and early part of the twentieth century the lightships had the means of making a signal to the shore if they saw a ship in distress. They would have a code which would avoid confusion and be clearly understood by the lifeboat coxswain ashore. If the Gull light vessel saw a shipwreck on the northern portion of the Goodwin Sands, one gun would be fired every three minutes. On the middle part of the Sands, a wreck would warrant the first gun fired then thirty seconds later a second one, this double signal being repeated every five minutes. For a vessel on the south part of the Goodwins one gun fired every five minutes; and if a ship was upon the north-west Sands, or the Brake sandbank, the signal would be two guns at fifteen seconds interval, repeated every five minutes. At night, rockets would accompany the guns.

Two days before the end of a very cold January 1919, the Gull light vessel’s cannons fired off her code along with a pyrotechnic display. Through the darkness there was hardly any need to advertise the position of the ship in distress. The 6,869 ton American ship Piave was aground close to the lightship with every light that she possessed switched on – lighting the ship up like a Christmas tree.

This had been the Piave’s maiden voyage from New York and she had her holds filled with much needed food for war torn Europe. Her cargo was to be landed at their next port of call, Rotterdam; however, without a pilot, the ship had inadvertently run up onto the Goodwin Sands.

At ten-thirty that night, William Adams launched the Deal lifeboat Charles Dibdin in a wind that was coming dead on shore from the East. Through the occasional snow flurries he had to sail on a long tack northward towards Sandwich Bay. He then changed course and beat to windward and reached the Piave an hour-and-a-half later. In the wintry elements his crew felt frozen. Three of them with numbed limbs, had difficulty in climbing the ladder that had been offered to them from the side of the Piave’s towering hull.

Dave Chamberlain

The lifeboat’s crewmen were dazzled by the ship’s deck lights, nevertheless, inquired as to the whereabouts of the ship’s captain. They were astonished, but accepted the courteous reply that he was sound asleep. Furthermore, they were informed that he was not to be awakened before seven-thirty the following morning.

Three Dover tugs had also arrived on the scene standing-by just out of the reach of the shallow water. They hailed the lifeboat and the salvage master was transferred onto her. Captain John Iron was not only Dover’s harbour master but also the Admiralty’s chief salvage officer and requested Adams to put him alongside the Piave.

Once aboard the ship, Iron demanded that the ship’s captain should be immediately awakened. Iron did his best to convince the captain of the seriousness of the situation and the urgency to get his ship off the deadly sandbank. Throughout the early hours the tugs’ hawsers were attached, however, the first attempt to pull her off failed.

After the futile attempt to tow the ship off, William Adam's crewmen willingly assisted the American crew to lighten their vessel. Overboard went sacks of flour, sides of bacon and vast slabs of lard. Soon after, three more tugs arrived and with all six now trying to pull the Piave off - they still could not move her. The icy wind had freshened and swung slightly to the south and a snow squall made their task a misery.

Although the salvage was still going ahead, the old lifeboat coxswain knew that there could be a chance that the vessel would be another Goodwin Sands victim. The Piave was straddled across the tide and the sand was building up amidships, leaving the bow and stern clear. He confided with the American captain that if he and his crew should have to abandon their ship he would transfer them to safety. On no account should they attempt to launch their own lifeboats.

1,500 tons of fuel oil was next to be pumped out. The oil would eventually kill hundreds of sea birds and pollute the beaches of Deal and Dover. Regardless of all these efforts the ship had stubbornly failed to budge an inch.

On the third day, at two in the afternoon, Captain Iron felt the ship quivering. He warned everyone that she was going to break in half. Whilst Iron was removing his salvage gear, the captain of the Piave entrusted him, with not only the ship’s papers but also £30,000. Two hours later the wind had risen to a strong blow and the sea-spray was being highlighted in the glare of the Piave’s deck lights.

With a noise not unlike rifle shots, the rivets on the hull in the engine room started to fly off. By four-thirty, the safety valve on the boiler burst. Next to break was the main propeller shaft. Within the following hour the ship broke in half and all of the lights were extinguished.

Above and below decks pandemonium erupted. The crew of 96 men panicked in the darkness and rushed around trying to seek salvation. Men jumped off the side of the hull as half of the massive ship fell over 25 degrees to port. William Adams, in the Charles Dibdin, knew his time for action had come.

When Adams heard the command to lower one of the Piave’s lifeboats he could not believe his ears. As soon as they made her ready 20 men scrambled aboard. Lowering the lifeboat the aft tackle gave way and, with a jerk, the boat hung in the falls by her bow. All of the 20 men were thrown into the rough, cold sea.

Chaos abounded – all around the weather side of the ship seamen were floundering in the water. Each and every one of the crew aboard the Charles Dibdin was busy with rescuing them. In the confusion there was a danger of people being crushed between the ship and the lifeboat. Another threat was the tide carrying them away into the night and lost from sight. Through the turmoil, Adams called to those aboard the Piave to jump into the Charles Dibdin as he sheered the lifeboat against the hull. He watched in disbelief when another two full lifeboats were launched from the Piave.

Fortunately the Ramsgate lifeboat had arrived, and between them they saved the Piave’s crew. The Deal boat cautiously towed the overcrowded ship’s lifeboat through the rough sea to the waiting tugs. With 29 of the Piave’s crew onboard, the Charles Dibdin then sailed for home, closely followed by the Ramsgate lifeboat with 23 rescued men.

****************

Skardon's World

History Stories

of

Deal, Kent, UK;

Written by David Chamberlain